Is Azure DevOps "Dead"?

Table of Contents

Introduction

You will have to excuse the hyperbolic title but I think there’s no fewer words I can use to accurately sum up the features of Azure DevOps (AzDo) compared to GitHub. Also, let me start this off by saying I, in no way, am paid by Microsoft to shill GitHub. In fact, both of these products are Microsoft products. But one (hint: it’s Azure DevOps) has been silently gasping for air for years. In the following article, I do not claim that GitHub reigns supreme among developer productivity or is the best toolchain. But there is no doubt in my mind that Azure DevOps has been put on life support.

Am I biased towards GitHub? I would argue no. I promise all I am biased in favor of is boring technology, turn-key solutions for myself and my team, and constantly evolving tools to handle ever-increasing complex, demanding problems. My mind is simple and the enemy of all developers is complexity; I want to do more with less because I like to build stuff people love.

I use Azure DevOps at my current place of work and as we look to the horizon to weigh all the options, I decided to take it upon myself to write this guide that will outline features that are missing in AzDo that I find incredibly useful in software delivery work. I’m going to favor things that are important to me and my current organization. This means features that are public-focused like GitHub Gists, which Azure DevOps doesn’t have but are awesome, or GitHub Boards (we use JIRA) aren’t going to be covered. The level of introspection and depth will vary but I can guarantee two things:

- I will assume you’re at least somewhat familiar with developer tooling and software delivery as to not have to waste words on preambles of setup.

- I will include examples in the form of pictures, code snippets, links to code, etc..

Okay, that’s enough putting up defensive walls and pre-explaining my position of what the hell this post is.

Let’s start from the beginning.

A Brief History

I’m not going to bore you with the details, but the short of it is this - GitHub was an independent product that was not owned by Microsoft long ago (in technology years). Skipping over the on-premise wars before SaaS products started really taking off, Microsoft developed Azure DevOps (once known as Team Foundation Server or TFS) as a competing cloud product, not just GitHub but also similar developer toolchain products like BitBucket, GitLab, among others. Continuous, automated building and deployment was exploding in popularity and the market demanded tools to accommodate the growing complexity and interconnectivity of systems.

As Microsoft was (IMO) pretty late to the game with their cloud offering, a lot of developers were already using GitHub to share their software. The open source software movement was exponentially growing and tools like GitHub were making it easier than ever to share & collaborate on common problems with code as solutions.

The timeline looks something like this:

- 2007 - Microsoft releases Team Foundation Services (TFS), an on-premise versioning system.

- 2008 - GitHub launches their service with a focus on open-source w/ a free model.

- 2012 - Microsoft becomes a significant user of GitHub for their repositories (.NET, MSBuild, Powershell, Visual Studio Code, and more). Other companies like Facebook and Google have overwhelming use as well.

- 2013 - Microsoft launches Visual Studio Online, a quasi-rebrand of TFS and a nascent Azure DevOps with a subscription model closely tied to Visual Studio. This gets re-branded again to Visual Studio Team Services (VSTS) along the way.

- June 2018 - Microsoft acquires GitHub.

- September 2018 - The service is finally called Azure DevOps and receives a free-tier that anyone can use.

Comparison Breakdown

The below sections can be read out-of-band but will often refer to other sections - it’s called a tool chain, after all. They are in no particular order except what came to mind first.

The CODEOWNERS File

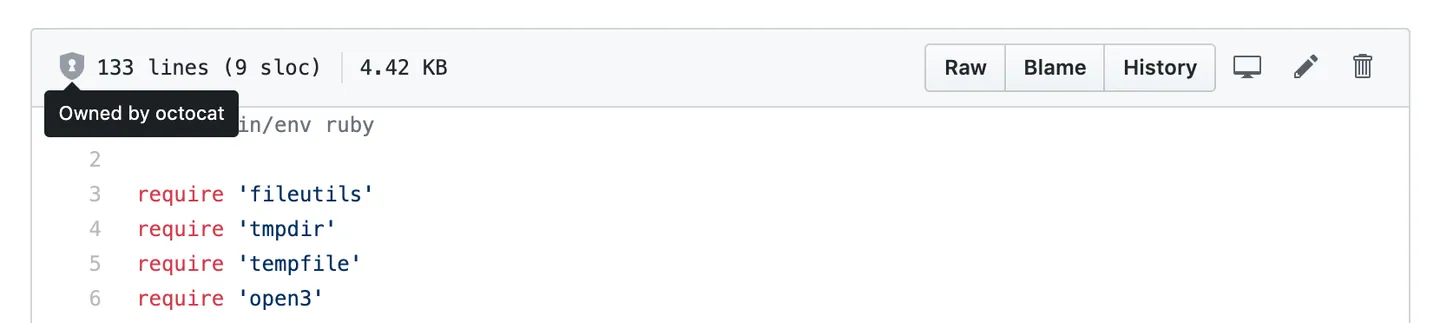

This feature, missing from Azure DevOps that but present on GitHub, is the CODEOWNERS file. Placing this file inside a repository automatically establishes ownership over the configured files and folders, with a lot of levers to pull for fine-grained control. What does this mean?

- Pull Requests that include changes to that code can automatically include the owners on the pull request as required approvers.

- Ownership can be viewed in the UI directly (without even really knowing about the CODEOWNERS file existing).

- The CODEOWNERS file can only be modified by the owner of the repository itself.

Ownership is visible when viewing files.

This is perfect for repositories with cross-team responsibilities and happens to align perfectly with companies trying to adopt InnerSource cultures.

Here’s an example of a CODEOWNERS file:

# This is a comment.

# Each line is a file pattern followed by one or more owners.

# These owners will be the default owners for everything in

# the repo. Unless a later match takes precedence,

# @global-owner1 and @global-owner2 will be requested for

# review when someone opens a pull request.

* @global-owner1 @global-owner2

# Order is important; the last matching pattern takes the most

# precedence. When someone opens a pull request that only

# modifies JS files, only @js-owner and not the global

# owner(s) will be requested for a review.

*.js @js-owner #This is an inline comment.

# You can also use email addresses if you prefer. They'll be

# used to look up users just like we do for commit author

# emails.

*.go docs@example.com

# Teams can be specified as code owners as well. Teams should

# be identified in the format @org/team-name. Teams must have

# explicit write access to the repository. In this example,

# the octocats team in the octo-org organization owns all .txt files.

*.txt @octo-org/octocats

# In this example, @doctocat owns any files in the build/logs

# directory at the root of the repository and any of its

# subdirectories.

/build/logs/ @doctocat

# The `docs/*` pattern will match files like

# `docs/getting-started.md` but not further nested files like

# `docs/build-app/troubleshooting.md`.

docs/* docs@example.com

# In this example, @octocat owns any file in an apps directory

# anywhere in your repository.

apps/ @octocat

# In this example, @doctocat owns any file in the `/docs`

# directory in the root of your repository and any of its

# subdirectories.

/docs/ @doctocat

# In this example, any change inside the `/scripts` directory

# will require approval from @doctocat or @octocat.

/scripts/ @doctocat @octocat

# In this example, @octocat owns any file in a `/logs` directory such as

# `/build/logs`, `/scripts/logs`, and `/deeply/nested/logs`. Any changes

# in a `/logs` directory will require approval from @octocat.

**/logs @octocat

# In this example, @octocat owns any file in the `/apps`

# directory in the root of your repository except for the `/apps/github`

# subdirectory, as its owners are left empty.

/apps/ @octocat

/apps/github

# In this example, @octocat owns any file in the `/apps`

# directory in the root of your repository except for the `/apps/github`

# subdirectory, as this subdirectory has its own owner @doctocat

/apps/ @octocat

/apps/github @doctocat

Bots

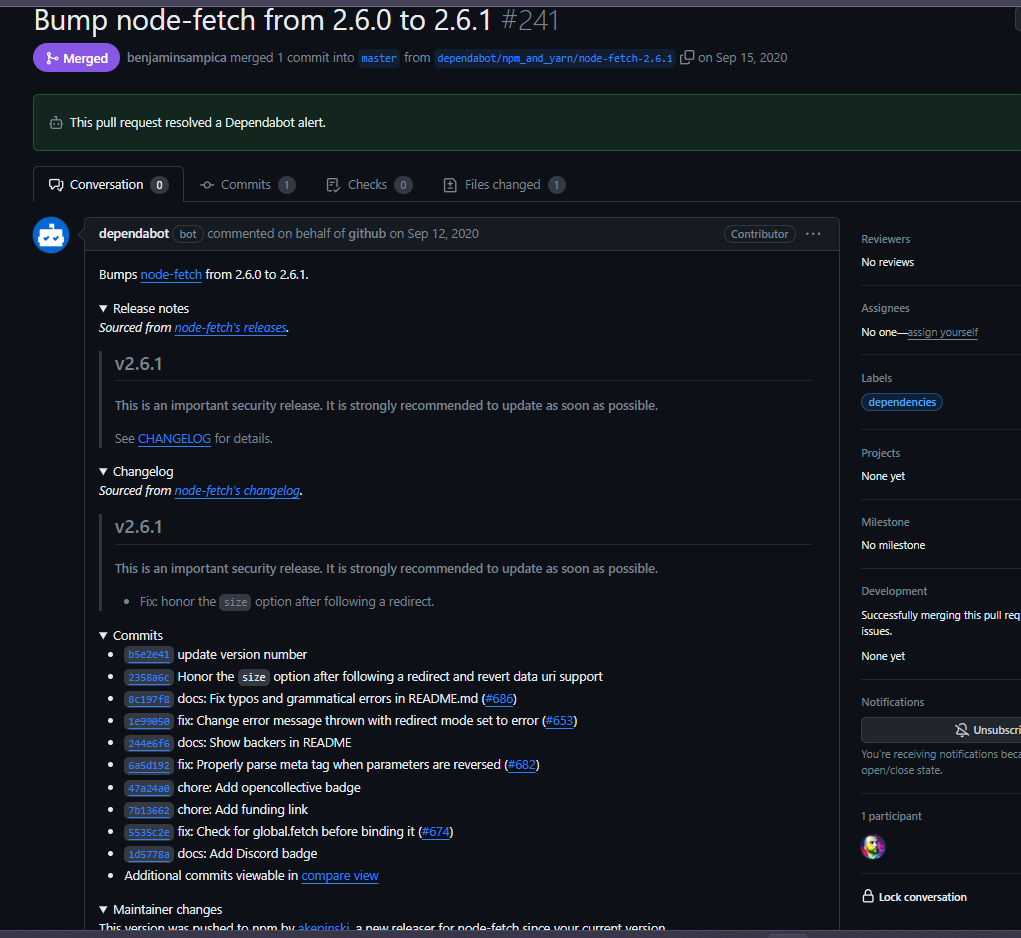

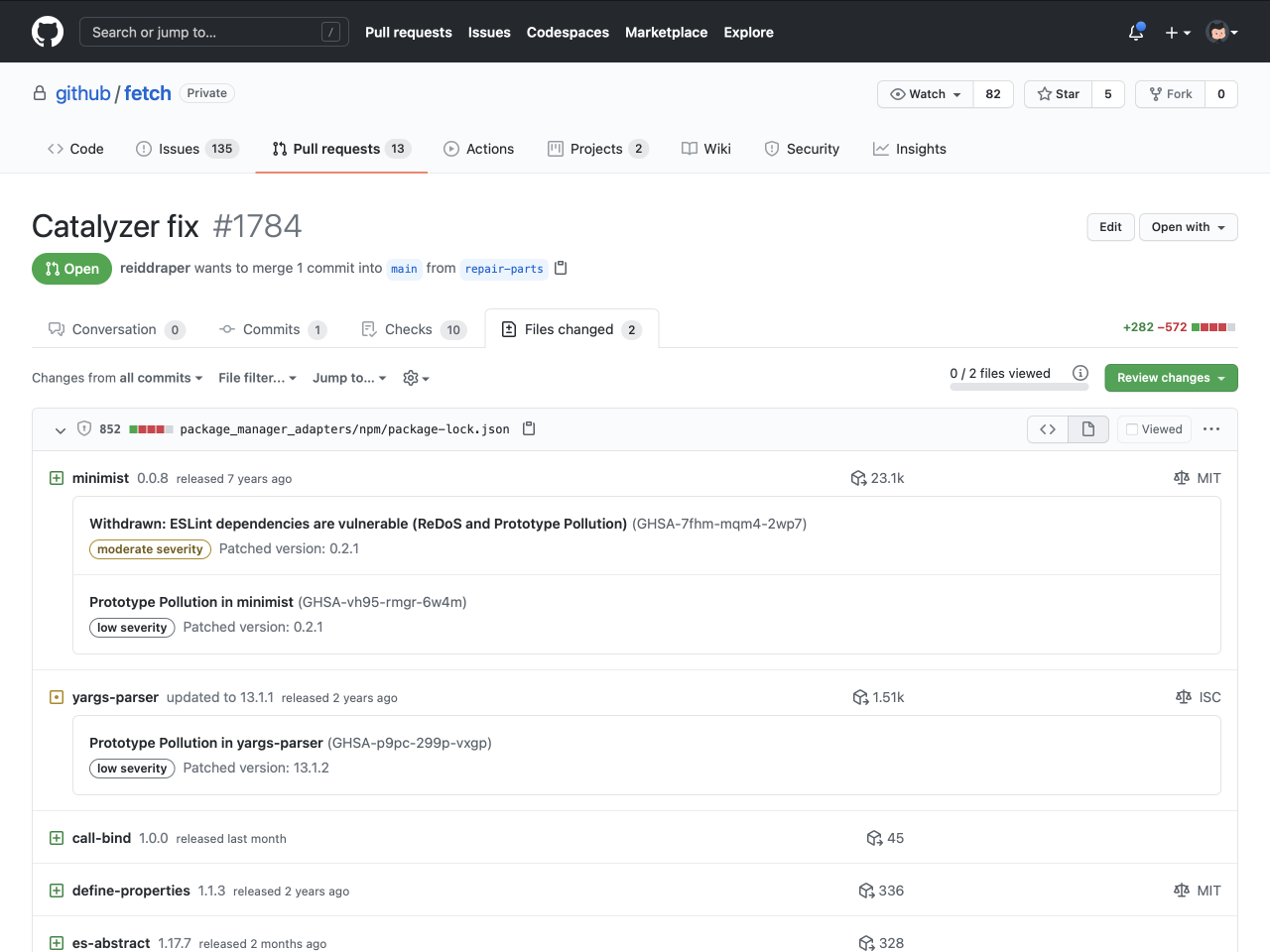

GitHub’s Dependabot is an automated dependency management tool integrated into GitHub and has been around for a number of years. It regularly scans your project’s dependencies for outdated packages and automatically creates pull requests to update them. This helps ensure that your project uses the latest and most secure versions of its dependencies. Here is an example of one of my own personal repositories of this in action.

Dependabot automatically opening a pull request for a security alert.

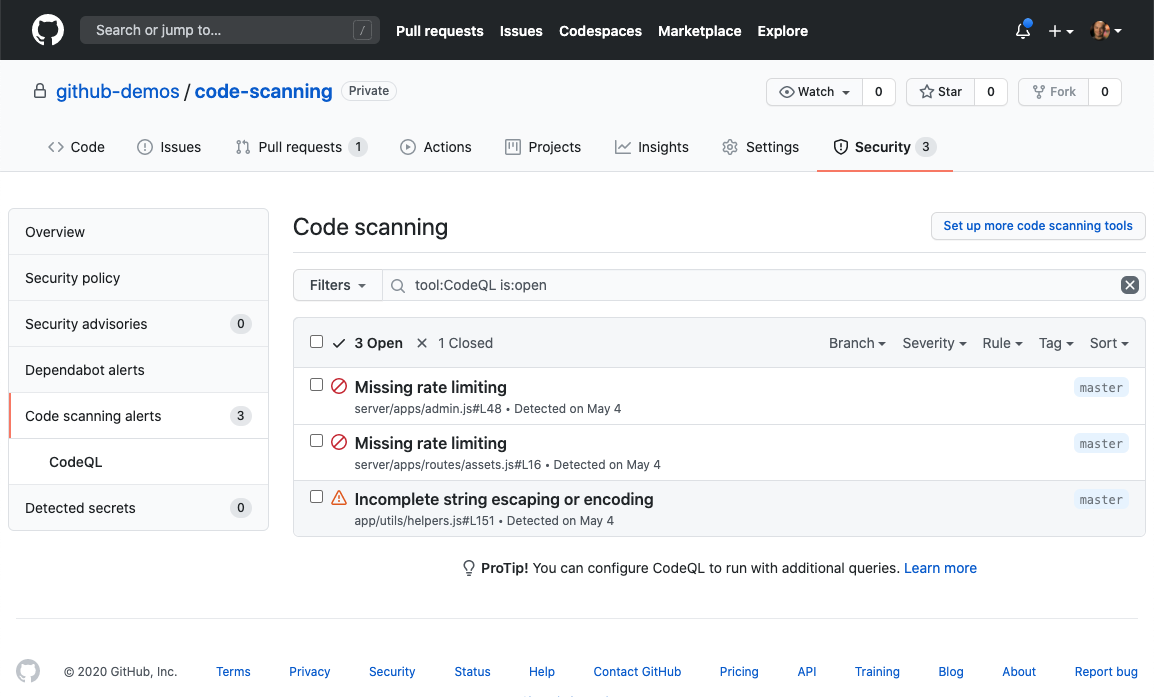

If you pay for GitHub Enterprise, they have a security feature called GitHub Advanced Security which provides the following capabilities:

- Code scanning - supercharges Dependabot to also find errors in code.

A code scanning example.

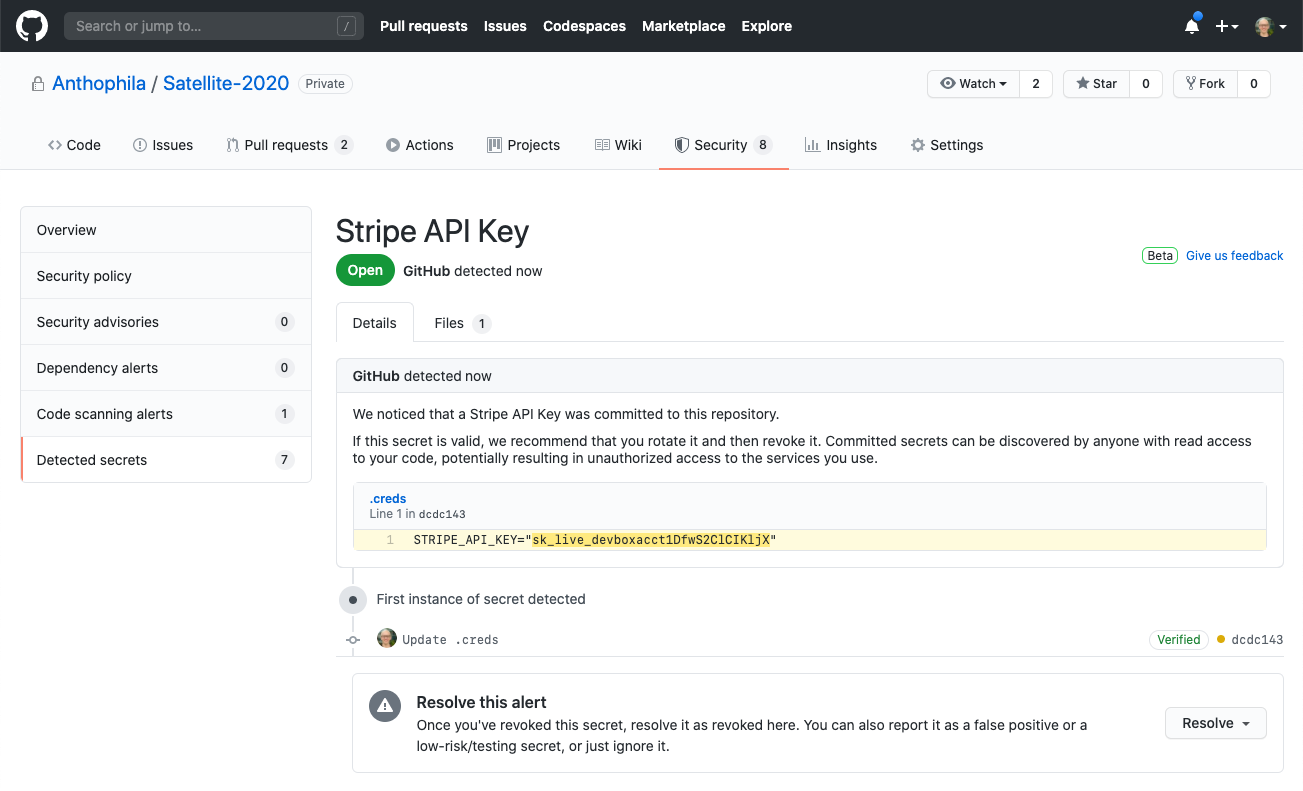

- Secret scanning - searches all repository branches, PR comments, and descriptions for private keys, tokens, and more.

A secret scanning example.

- Dependency review - shows a comprehensive list of dependencies in every pull request as well as your dependencies security alerts.

A dependency review example.

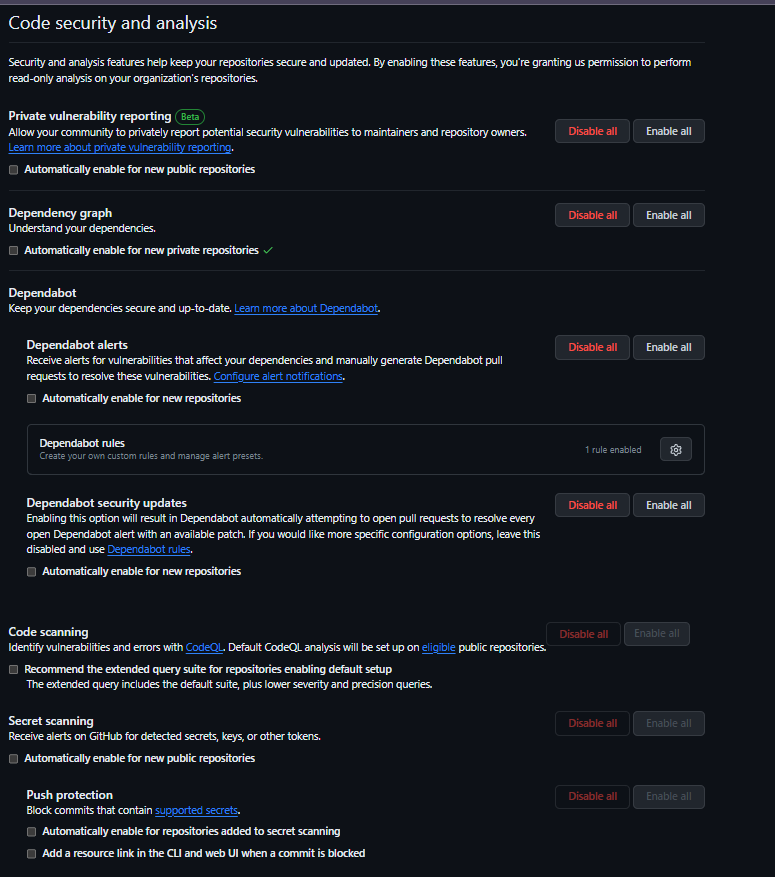

And finally, a comprehensive list of all these settings in GitHub with GitHub Enterprise.

Code and security analysis options.

A few weeks ago (October 2023), Azure DevOps just implemented some of GitHub’s Advanced Security features outlined above with an additional $49/user/month subscription cost.

That being said, the level of botting capability in GitHub is high. It is common in GitHub to have bots help with pull requests, code reviews, and branch management - typically things left entirely to the developer team. For example, the pr merge bot can block merging of a pull request based on a label do-not-merge. Additionally, the reginald pr bot can block merging of a pull request if the pr doesn’t contain a title like [JIRA-2100]. Finally, the action git diff suggestions can run a linter automatically on the pull request and then will automatically push a commit to the PR with the linted code, and much more.

Maintaining Documentation

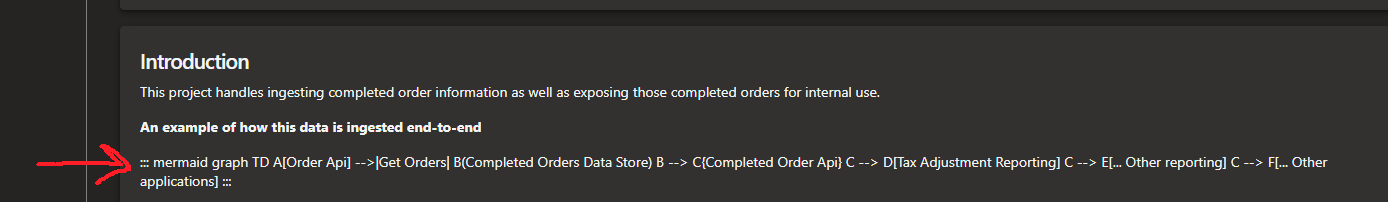

Azure DevOps supports readme files being composed with markdown in their repositories. They even claim to support graphs, which are “officially” supported but broken where it matters… actually viewing them.

A mermaid diagram that should work but is broken. Sad.

However, readme files cannot be comprehensive (it is a single file, after all) and additional long-form written repository documentation has to sit further away, in AzDo’s Wikis section which, annoyingly, implements the same security permission structures that the project uses (this decoupling is also present in secret and variable management). If your project has a global repository setup to protect your main/master branch (very common), you have to submit a pull request just to update documentation.

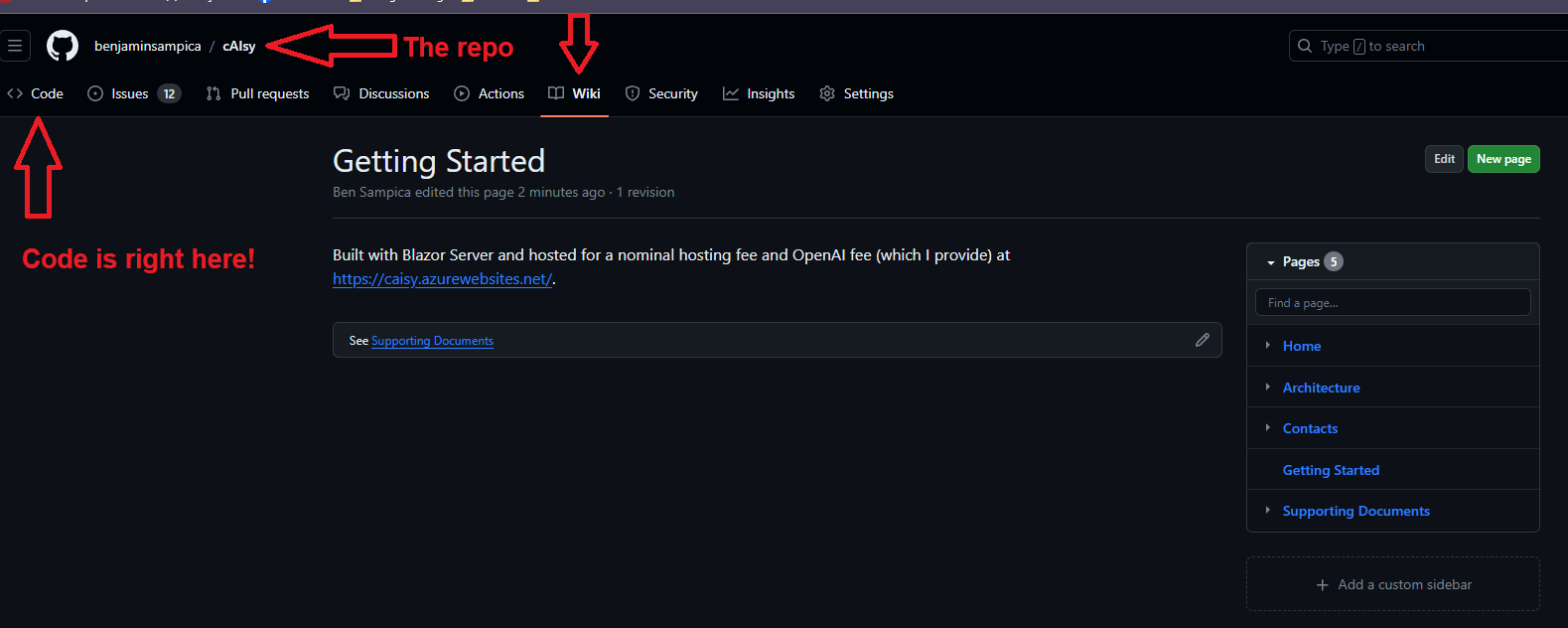

In GitHub, each repository has its own Wiki so this documentation can sit much closer to the code (the principle of proximity playing a role here) but doesn’t inherit the same git protections as the repository itself. However, only those with write permissions to the repository can contribute. As a bonus, the diagrams actually work, too.

Wiki's sit at the repository level.

Extension / Task Marketplace

The Azure DevOps marketplace contains very few up-to-date tasks or tasks that simplify common work. As of November 2023, there are only 2241 extensions available on the marketplace - this includes both extensions to Azure DevOps itself and also pipeline tasks. The majority of these have not been updated in the last two years.

The built-in tasks for Azure DevOps are sorely lacking both in breadth and maintenance. There are a wide array of core tasks that have never made it past alpha, such as AzureAppServiceManage@0, IISWebAppDeploymentOnMachineGroup@0, and SqlDacpacDeploymentOnMachineGroup@0. You can view all their tasks here.

On the other hand, GitHub Marketplace has over 20,000 pipeline tasks alone, like the ability to login to cloud providers, deploy function applications, build caching, and much more.

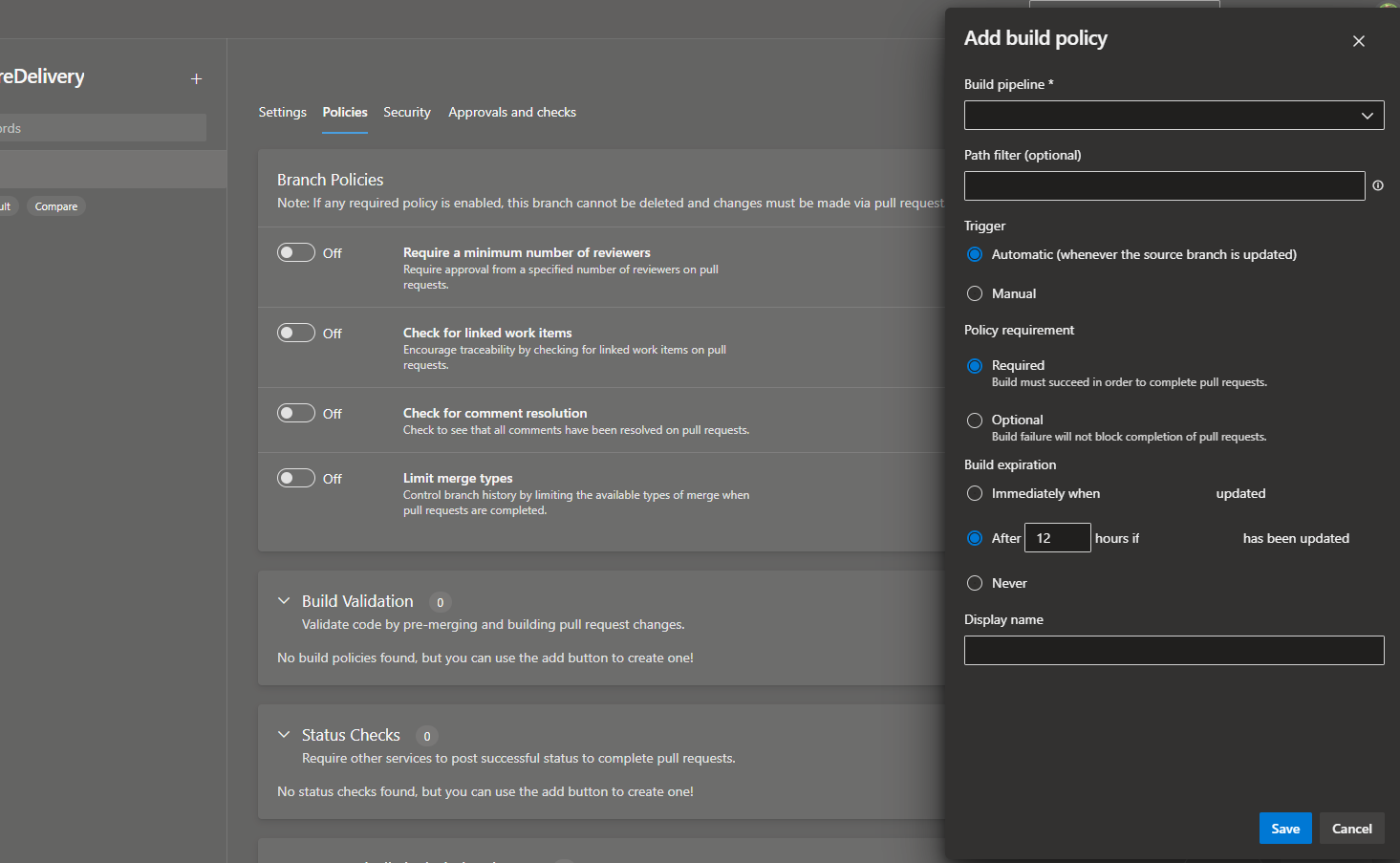

Creating & Managing Build Validation

One of my biggest pet peeves with Azure DevOps is that build validation is managed outside the repository YAML file in Azure DevOps, which brings in the necessity for additional security permissions and controls to be in place.

# Azure DevOps YAML File

trigger:

batch: true

branches:

include:

- main

tags:

include:

- v*

# Can't add pull request validation, see image below.

Require builds to succeed in order to merge code in Azure DevOps.

In GitHub, its properly placed in the workflow file and can be managed by change management the same way as the other parts of the pipeline like the example below.

# GitHub Workflow YAML file.

on:

push:

branches: [ main ]

tags:

- 'v*'

pull_request: # This is not possible in Azure DevOps

branches: [ main ]

Creating & Managing Pipelines / Workflows

There are some features in Azure DevOps that remain unimplemented or half-baked when it comes to Pipelines. For example, Azure DevOps has the concept of secure files in order to be able to download and read files (like certificates) during pipeline runs. There is a feature underneath secure files called Properties which is completely undocumented and appears to be unusable. It would be great to store certificate passwords alongside their secrets, but at the moment this is impossible (and has been for at least four years).

Additionally, pipelines themselves must be associated manually with yaml files located in repositories which is just another place where they need their own permission structure (like secrets, build validation, and documentation).

In GitHub, workflows YAML files are discovered automatically when committed to the repository.

I’m not going to dive into all the ways that GitHub Actions allow much more expressive YAML pipelines which simplify some jankiness and verbosity of Azure DevOps but you can look at the examples here or even plug in your own YAML files and watch them shrink. However, one feature I do want to call out that is present in Github Actions (and not Azure DevOps) is the multitude of triggers that are supported. For example, you can trigger workflows based on pull request reviews being submitted, declined, labels added, and so much more. For example:

on:

pull_request: # Will trigger on any of the below labels being added to the PR

types:

- labeled

- ready_for_review

- review_request_removed

- review_requested

- synchronize

- unlabeled

pull_request_review: # Will trigger on a PR review being submitted or dismissed.

types:

- dismissed

- submitted

These types of triggers play right into bots, of which there is a lot of capabilities available to automate a lot of mundane repository or code tasks.

Secret / Variable Management

Like the Documentation section, pipeline secrets and variables in Azure DevOps are managed outside the repository in the Library section, with their own permission structure. Secrets are “optionally” secret and must be manually locked in order to actually hide them and must be replaced. If they aren’t locked, they’re a variable and viewable.

However, in GitHub, secrets and variables are two separate things and referenced in two separate ways in workflows. Secrets, once set, are always secret and only can be replaced. Advanced GitHub features pair really well here to make sure secrets always stay secret and that people aren’t accidentally setting secrets as variables (see the Bots section).

GitHub also has the capability of adding organization secrets & variables, notably missing from Azure DevOps. These secrets & variables can be brought into any pipeline across the entire organization, but managed by a core team (like an Identity Access team).

Artifact Registry

Azure DevOps and GitHub both provide common package hosting for shared libraries like NuGet and npm packages. However, GitHub also provides container hosting as part of their offering which is called GitHub Packages that helps reduce the amount of novel tooling needed to host and share containers throughout an organization.

The Service’s API

Have you tried to use Azure DevOps’s API to do things? At best, you’ll find documentation that is only slightly out of date with their actual API. At worst, you’ll find some random thread off of Google where an answer recommends using a “hidden” API with only a HTTP verb and a URL as your north star. I’m particularly salty about this one as I tried to programmatically migrate repositories from one Azure DevOps project to another over a year ago and found it hilariously frustrating to pull off (if I didn’t laugh about it, I’d cry). GitHub’s API has some faults, but the documentation has been solid every time I have used it.

Security wise, GitHub allows much more fine-grained control over personal access tokens that are used to authorize with the GitHub API compared to Azure DevOps, enabling a least-permissive approach. Additionally, check out the Bots section to see the automatic protections in place for secret leakage.

Adoption

I’m not going to pull out all the different adoption metrics GitHub has as it’s absurd (100million public repositories, for example) so I’ll stick with a personal anecdote. I just finished attending .NET Conference 2023, run by Microsoft itself, a few weeks ago. These folks are the prime candidates for using Azure DevOps - Microsoft employees, .NET Developers, overwhelmingly use Visual Studio, and Azure. All throughout the conference, every speaker that gave a presentation besides a single one was using GitHub to share, host, and deploy their code.

As an aside, of those that were visible, there were more MacBooks than Surface’s too 🤔.

Templating Repositories

Azure DevOps has no templating capabilities besides old-fashioned cloning.

GitHub allows you to create template repositories that can be used as a starting point for new projects. These templates can include files, directories, and even default issues or pull requests. This helps maintain consistency across projects and saves time on initial project setup; it is something I have used at every step of my career. As a bit of trivia - this website itself was generated from a GitHub template.

bensampica.com's template.

Auditing

Azure DevOps’ Auditing has a narrower set of events it tracks for users but is probably adequate for most organizations. However, they only store audit logs for 90 days and only let you filter by a date range.

In contrast, GitHub Audit Logs have a wider set of events that are tracked but the power really comes in how you can query them. All event categories can be filtered on, including searching by user, correlation id, repository, and much more. Additionally, you can use arithmetic operators like > and < to search ranges (like dates), = to search for specific keywords, or - to exclude things. As an added bonus, GitHub also stores audit logs for 6 months which could narrow down the window that you need to ship them somewhere else (but no worries the API is good).

Summary

So is Azure DevOps “dead”? No, of course not. But I hope you at least understand where I’m coming from. A vast amount of features are missing from Azure DevOps and, looking at their lean list of things shipped in the last few years, likely never coming. Since using the above features in my daily work, I consider them to be vital tools to do more with less and reduce toil whilst operationally increasing security.

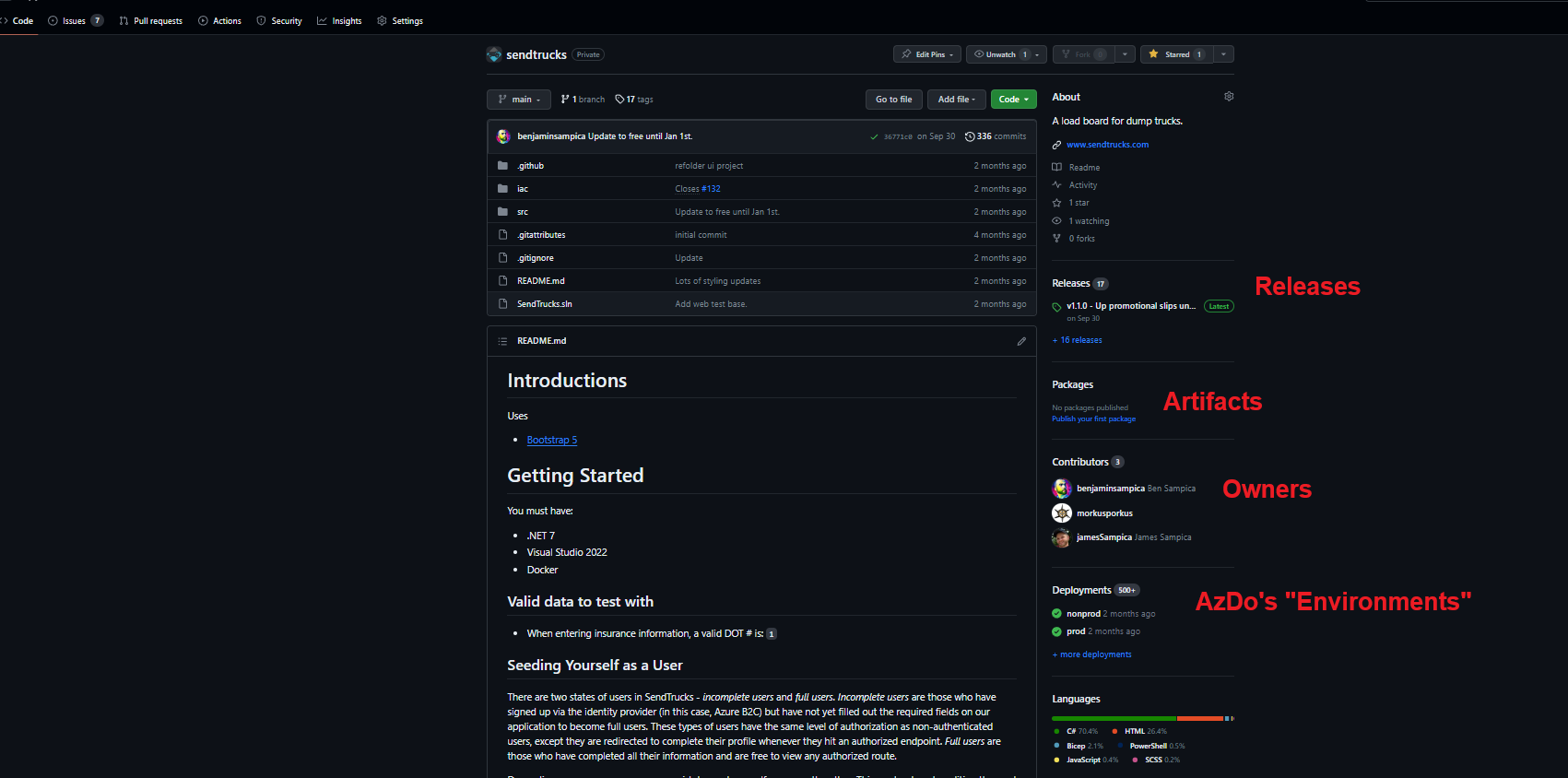

Underneath a lot of these missing features is fundamentally a difference of approaches, which can really be summed up as this: Azure DevOps views its “Projects” as the center of the universe, with the management of Wikis, the variables/secrets in its Library, as well as builder & releaser of Pipelines and Repos as all each being different people and little overlap. GitHub views the repository itself as the center of the universe and is structured as such - most of the information that is a dozen or so clicks away is readily available on a single page at the root GitHub repository, with most other information one click away.

GitHub's repository root page.

That is not to say that GitHub Organizations and projects don’t wrap repositories up into configurable units with global policies, but that GitHub has strongly modeled itself with the premise that the creation, management, and deployment of code at the repository level has shifted-left to a single team in the majority of cases instead of Azure DevOps’ “programming team”, “release team”, and “support team” user interface layout.